Now that the differences between 18th century minchiates of the Florentine and Bolognese patterns have been identified, I want now to look at them in the context of an historical development: where did they come from, where are they going?

I have already said about as much as I can about where some of the woodcut designs go: it is into a new version of the old engraved depictions: we have seen this in the man's arm in the Tower, the halos on the theological virtues, Faith's spear, the animal's direction on Fire (although other cards reverse right to left without prompting from the woodcut designs), the overall designs of water, earth, and air, and the wrap over the World-angel's genitals. In addition, Papi 2 and 3 of the later lack the monstrous animals at the feet of their equivalents in the former; since they are absent from the woodcuts, their economy may have made a contribution. In two subjects the later engraveds redesigned the cards completely, taking a woman standing by a column for Strength and two naked soldiers on Gemini. It is perhaps for these cards that the deck is termed "neoclassical"; I can't think of anything else, as the previous engraveds veer toward the two 17th century trends of naturalism (as opposed to mythology) and the baroque ornateness.

I have already said about as much as I can about where some of the woodcut designs go: it is into a new version of the old engraved depictions: we have seen this in the man's arm in the Tower, the halos on the theological virtues, Faith's spear, the animal's direction on Fire (although other cards reverse right to left without prompting from the woodcut designs), the overall designs of water, earth, and air, and the wrap over the World-angel's genitals. In addition, Papi 2 and 3 of the later lack the monstrous animals at the feet of their equivalents in the former; since they are absent from the woodcuts, their economy may have made a contribution. In two subjects the later engraveds redesigned the cards completely, taking a woman standing by a column for Strength and two naked soldiers on Gemini. It is perhaps for these cards that the deck is termed "neoclassical"; I can't think of anything else, as the previous engraveds veer toward the two 17th century trends of naturalism (as opposed to mythology) and the baroque ornateness.

It used to be thought that the earlier of the two engraved patterns arose in the second quarter of the 18th century and for that reason had to be later than the "earlier" woodcut pattern, which went back to the 17th century. But Monzali (in part 1 of his article cited in the Introduction) has shown that the early engraveds, by virtue of the signatures on the cards, might go back as far as 1682. That puts them potentially as early as the sheet of uncut cards given to that century, although I see no good reason why they might not be of the first quarter of the 18th. If so, what is the basis for saying that the "earlier" or woodcut style is earlier than the early version of the engraved pattern?

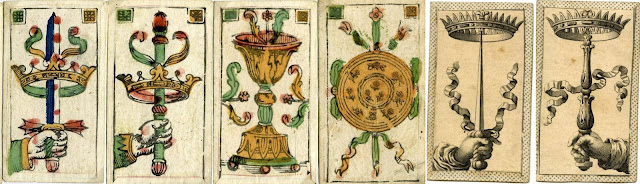

I want to try to answer this question by situating the two historically, in relation to the sources that inspired them. First, it must be said that interlocking straight Swords go back at least as far as the separated Swords of Bologna and the engraved. We see them in the Visconti di Modrone, ca. 1442 Lombardy (online under "Visconti cards" at the Beinecke Library), continuing with the Visconti-Sforza of the 1450s (Morgan Library). In between are the Brera-Brambilla with curved Swords (not shown, but also with connected hilts). We see curved Swords in the Rosenwald (downloaded from the National Gallery in Washington D.C.), dated to around 1500 or a little after, and the Budapest-Metropolitans (from block T3 at https://cards.old.no/irwpc/). We are back to straight swords (if they ever went away) in the cards of Padovano in 1547, in cards with the little figures interspersed quite reminiscent of minchiate, in this case of its 2 of Batons. All have interlocking sword hilts.

That the Sword on the Ace would pass through a crown, perhaps with other decoration, is again ancient, so at least not invented by our anonymous engraver. Below are all four aces in the Rosenwald, along with another Ace of Coins that matches ours better, from Budapest-type sheet F1 at https://cards.old.no/irwpc/. In this case the arm comes from the left. In another sheet, also with centaurs for Knights and reproduced by Franco Pratesi at https://www.naibi.net/A/526-ASSISI-Z.pdf, the arms come from the right. On sheet F1, the arms come one from the left and the other from the right. On another sheet, Budapest-type R1 (for "reversed"), they are the opposite. On another, the "Elegant," it is the left again.

But in Cups and Coins, it is rather clear that the engraveds are a major

departure from the past, which both the woodcuts of both Florence and Bologna are closer to. The engraved Aces of Coins and Cups have elaborate scenes on them, as on medallions and ancient urns. They are obviously the engraver's own innovation.

In Coins, the Padovano cards shown by Depaulis ("Hidden treasures in the Musée du Petit Palais, Paris," The Playing-Card 45, no. 3 [Jan-March 2017], p. 180) and Monzali (for the 4 of Cups, in his part 1, p. 18) use a floral design seen later only in those Bologna-pattern decks without the name of a city in their 4 of Coins, e.g. first below (except Endebrock's, which has the "cogwheel" pattern, not shown), or which have "di Roma" (second below) Those with a brand-name on their 4 of Coins and most of Florence's have heads, whether the elephant faces forward (Poverino, middle) or to the right (Colomba, 4th), except the Etruria decks which have eight-pointed stars (far right). On the Budapest-style sheets, the floral pattern is most prevalent, but eight-pointed stars are also seen. When heads were introduced is unclear.

A unique thing in the engraveds' suit of Coins is that it has pictures

of birds rather than the usual human heads on the 8s. This innovation

may be related to the same phenomenon in a tarocchini deck created by

Giuseppe Mitelli in 1660s Bologna which does the same, only on the 6s. In the engraved version of Cups, the suit-signs in Cups sprout handles. Similar handles are in the Mitelli. Another parallel is how they both make handles disappear occasionally.

The woodcut Kings and Queens conform to traditional models seen in the two decks mentioned. The Assisi deck mentioned earlier has bearded kings of Cups and Coins and unbearded Swords and Batons. Other decks have all the kings unbearded. However, they are almost always sitting. In the engraveds, both the Queens of Cups and Coins are standing. In Mitelli's deck, all the Queens are standing, as well as the King of Coins. He also includes on the card a cabinet just high enough to put a cup on. This is another feature shared by our engraved minchiate.

We might also look at Mitelli's World card in relation to the engraved minchiate's Knight of Coins. In the woodcut version, he holds his coin as if it were quite light. In the engraved, it is over his shoulder and appears heavy, like the sky to Atlas and Hercules (below, the Etruria, early engraved, and Mitelli.

Another card where Mitelli and our engraver are similar is the Fool. The woodcut (the two at the right below) did not have the "windmill" toy raised by the engraved Fool (although the Bolognese has one more toy, a wooden duck-head, not very clear in the "in Bologna" subtype); nor did the standard tarocchini Fool (a drummer, not shown here), but in Mitelli's version the same "windmill" is prominent. At the far left is a child with the same toy, in a painting by Hieronymus Bosch.

Historically, the direction of the hand of the child on our right might

be important, pointing at the main figure's crotch. That gesture is

prominent in a couple of tarot types: in the d'Este 15th-century

hand-painted version (its heraldry suggest it was done to commemorate a

d'Este-Aragon marriage), the child is touching the man's penis; in the

TdM, it is an animal that is attracted to that area. It was the symbol

of masculine fertility in ancient times, well known in Ferrara. Why it

should be related to the Fool is unclear: perhaps because it is not

given much to thinking.

Historically, the direction of the hand of the child on our right might

be important, pointing at the main figure's crotch. That gesture is

prominent in a couple of tarot types: in the d'Este 15th-century

hand-painted version (its heraldry suggest it was done to commemorate a

d'Este-Aragon marriage), the child is touching the man's penis; in the

TdM, it is an animal that is attracted to that area. It was the symbol

of masculine fertility in ancient times, well known in Ferrara. Why it

should be related to the Fool is unclear: perhaps because it is not

given much to thinking.In the trumps, Papa I in the woodcuts is the typical tarocchi figure standing at a table on which are the implements of his trade. His being surrounded by children (unlike in the Rosenwald) goes back very far, as indicated by a line in a ca. 1539 poem giving a stanza to each of 40 prostitutes in Florence (see edition of Danilo Romei, I Germini sopra quaranta meritrice della città di Fiorenza, Nuovo Rinascimento, 2020, p. 108, in archive.org): "Io son di Boncio la povera Lena, / che sostento que’ bambini e non posso" (= che sostener quei bambini non posso, per Romei p. 160, so "I am of Boncio the poor Lena, that to support the children I can't").

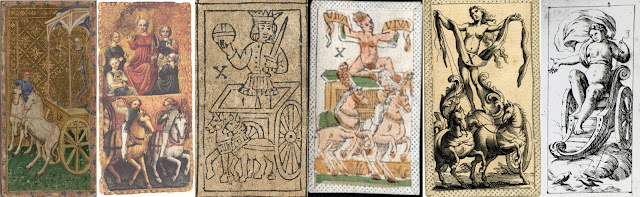

The woodcuts of Papi 2, 3, and 4, are quite similar to the corresponding

papi of the Bolognese tarocchini (above, the "Dalla Torre" of ca. 1670-90), which themselves are elaborations of trumps 3, 4, and 5 of the Rosenwald. Papa 2 even has a similar tilt of the head. It is not known how old the former

are, but Dummett thought by at least by the early 16th century, based on their similarity to the Rothschild-Beaux-Arts sheets of ca. 1500. That Papa 4 was thought of as the pope early on is indicated both by the poem by Bronzini reported by Renzoni (see my previous section) and in the poem assigning cards to prostitutes: "sol la mitera un po' portai allora," I only bore the miter a little then. A miter is the headdress of high church officials. Of course at some point the figure lost the papal crown and took the imperial one instead. And only in the Etruria does he get an imperial tripartite orb (signifying Europe, Asia, and Africa, as in the Florentine "Triumph of Time" at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Petrarch%27s_triumphs#/media/File:Petrarch-4-fame-justice-florence.jpg.) In recompense, he gets an imperial eagle, insignia of ancient Rome as well as both of its successors. I am not familiar with an orb divided into two, whether by a double line as in Bologna or with colors and shading as in Florence.

In the engraved, the performer leans over to observers on one side. Among early Italian tarocchi, the only precedent I know is the 15th-century d'Este hand-painted card (2nd below). Even though the d'Este were of Ferrara, some experts say that this deck was made in Florence. Papi 2, 3, and 4 are just reworkings of the woodcuts - which surely came first because of their greater closeness to the tarocchi from which they sprang - with the addition of fantastic animals.

A precedent for the animals is the seven virtues of the "Tarot

of Mantegna," each of whom is accompanied by an animal, sometimes

fantastic.

That Temperance pours liquid from one vessel to another in a gravity-defying manner, Strength wrestles a lion, and Justice holds a scales,and prudence a looking-glass and serpent is from the medieval tradition of illustrating the four cardinal virtues, the first three well established in the 15th century tarocchi. Since the lion was associated with Samson (as well as Hercules), the broken column is a natural symbol of the same virtue of Strength, from his bringing down the temple of the Philistines.

The Charles VI shows both halves of the column, like most of the woodcuts but not the engraved; the lion at the bottom is absent from the tarocchi of Florence and Bologna, even if present in Milan and the Budapest-Metropolitan sheets. Its most likely source, however, is the "Tarot of Mantegna" image of Fortitude, which also has both parts of the column (see previous image above).

The woodcuts' Wheel is quite traditional, seen in many early examples (Modrone, Brera-Brambilla, Budapest-Metropolitan), where donkey ears or at least body parts are on all the participants on the Wheel. The engraveds' replacement of the figure going down with Fortuna herself, recognizable by her long hair in front, is an innovation; the proverbial "taking occasion by the forelock" was a popular 16th-17th century motif of the emblem books, sometimes with a wheel. Its use on a tarot card is another commonality between Mitelli and our anonymous engraver.

An Old Man on crutches was familiar both from the Florentine-Bolognese tarocchi tradition and the illustrations of Petrarch's I Trionfi seen in Florence. Crutches are also referred to in the poem about the prostitutes for this card, p. 86: "vo con dua grucce, come ciascun vede," I go with crutches, as everyone sees." The stag probably comes from the animals chosen to drive the illustrations' chariot, and the clock from the same sources (below is a wedding chest panel by Jacob Sallaio). I have not seen the arrow otherwise, but the "arrow of time" is a common enough metaphor. It seems to replace the wings, which were never part of the tarot tradition.

On Death, the lack of a right leg of the main figure was a noticeable difference between Bologna and Florence. This same difference can be found in ca. 1500 woodcut sources.

In the ca. 1500 Florentine short tarocchi poem naming all the tarocchi subjects (Depaulis in "Early Italian lists"), it is simply "Saetta," meaning both "arrow" and "lightning." Earlier cards, such as the Charles VI and the Rosenwald (the latter at left), did show lightning hitting a tower and causing it to crumble, as flames leap up. The poem with the 40 prostitutes of Florence calls it "quella Torre che par proprio di fuoco una fascina," that Tower that looks just like a bundle of fire (p. 78). The Rothschild sheet (its 17th century version is almost the same) show a building on fire and two men losing their balance. There is no suggestion of any "devil" attached to these buildings, although it might be some sort of destruction from a divine source. So what happened?

"House of the Devil" is first attested in a ca. 1520 poem addressed to the ladies of Ferrara. Exactly what the card there depicted is not clear. The Budapest sheets, thought to be from nearby Venice, show a tower with an open door, but no people. Its red color makes it look like a "bundle of fire" indeed. Yet a late 15th century series of illustrations of biblical events done in northern France, shows for the Tower of Babel sa devil inside the doorway of such a tower and two people falling from its heights, rather similar to the "Maison-Dieu" card of the Tarot of Marseille (http://pre-gebelin.blogspot.com/2013/02/lydgate-mans-lot-in-life.html).

Next are the three theological virtues. Halos on virtues are seen earlier in Florence's cassone tradition, i.e. wedding chests of the "seven virtues," and in the Charles VI tarot. Why the engraver would take them off the theological virtues is unclear, unless he wanted a more natural (as opposed to supernatural) appearance, or was following the lead of Mitelli or the Bolognese tarocchini. The later engraved version put them back in.

Exactly what inspired the iconography of the minchiate's theological virtues is unclear, because the imagery was so ubiquitous. In Florence itself, one possibility is the paintings of them by Piero del Pollaiuolo, ca. 1479, for the Signoria of Florence (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piero_del_Pollaiuolo#, find "seven virtues").

Hope lacks a crown, but otherwise the Bolognese versions - and the Florentine were the same, except sometimes for Faith - are merely a simplification of these paintings. For the crown on Hope, there are other sources, such as Giotto's Hope (1st below).

And before Pollaiuolo, there was the Visconti di Modrone (above, 2nd through 4th), similar in all respects regarding what is depicted.

Before that was a funeral monument attributed to Giovanni dal Ponte (above, taken from the book Giovanni dal Ponte, 2016, p. 36), whom many think was the artist who created the earliest known tarocchi-like deck, surviving today as the Rothschild cards. The latter is mostly court cards of an archaic type, but there is one card with a strong resemblance to the Charles VI's Emperor card (1st and 2nd belowt), albeit lacking the illusion of depth possessed by the latter. Exactly when the funeral monument was done is not known, but Dal Ponte died around 1437. The monument, installed in Florence's cathedral, was for a certain Cardinal Pietro Corsini, whose remains were transferred there from Avignon after his 1405 death in Avignon.

In any case, one should not rule out a continuous transmission through the earliest time of the game, with the Modrone as one manifestation. For Faith, my hypothesis is that in minchiate a monstrance, i.e. a container for holding consecrated communion wafers, substitutes for the communion cup. If so, the oval shape in Bologna and sometimes Florence communicates that object far better than a kite, although the straight lines of the latter would be much easier to cut. If the fuzzy lines on the Poverino (3rd above) denote a cross, that was one of Faith's attributes, too.

Compared to the woodcuts, the engraved of Prudence and Faith (2nd and 3rd above) seem like a product of invention. The swirl of fabric behind Charity is something that occurs frequently in the engraveds. It is the same for Mitelli, as can be seen for example in his Chariot, shown earlier.

Compared to the woodcuts, the engraved of Prudence and Faith (2nd and 3rd above) seem like a product of invention. The swirl of fabric behind Charity is something that occurs frequently in the engraveds. It is the same for Mitelli, as can be seen for example in his Chariot, shown earlier.

Then come the four elements - unlike the theological virtues, these do not have an established symbolism. The Rothschild-Beaux-Arts sheet World card shows the four elements in the circle of the cosmos: very basic, of course. Otherwise, there were the medieval bestiaries, whose art the woodcuts somewhat resemble; in them, certain animals had an affinity for certain elements: land animals with earth, sea creatures with water, birds for air, and that is what we see on the cards. Trees and buildings for earth and clouds for air are of a similar sort. The poem about the prostitutes speaks of a "pine tree" in the Earth card and "stars" in the Air card. That could correspond to any of the 18th century versions of the card. The scene on the engraved Earth is like a Dutch or French landscape painting of the 17th century. The entirely schematic woodcut for Air - typical of the early tarocchi - becomes more realistic in the engraved. Only the animal at the bottom is incongruous, but he takes on the role of a landlocked onlooker.

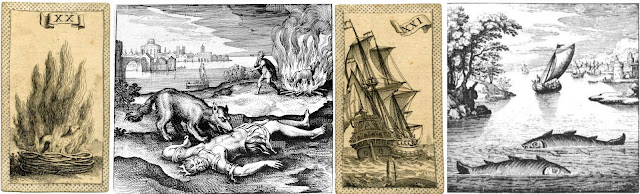

For Fire, the animal par excellence was the salamander, said in the Renaissance and before to thrive on fire (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_depictions_of_salamanders#, section "The Renaissance") Perhaps at one time the animal on the Fire card was a salamander. But the closest image I can find to the current card is an alchemical image from the Atalanta Fugiens of Michael Maier published in 1618 showing a wolf eating a king, being consumed by fire, and revitalizing the king. It is a metaphor for the purification of metals, but also corresponds closely to the card. I imagine that an earlier version had a salamander instead, now moved to the Air card. The poem about prostitutes doesn't mention an animal in relation to either card but does speak of the four procuresses of the group (each managing nine women) as "the four salamanders" in the introduction (p. 26, stanza 4), with the implication that they are wise about life and the ways of the world. Apparently these salamanders were mythical beasts of great wisdom.

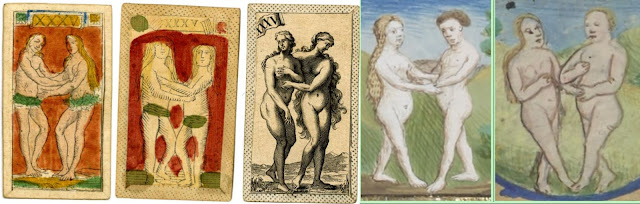

He did not modify Gemini as much, but he did pick the one accepted version, by the 17th century, whereas the woodcuts picked a different one that had also been popular. shown in some of the images in the threads just given plus Sandy's thread at https://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?p=20561#p20561. Books of hours often showed either two boys wrestling or a boy and a girl embracing, both nude in either case and facing each other. Yet sometimes they were shown facing the viewer, the way that became standard later. The Florentine standard woodcut card used the former, while the engraved, and a few of the woodcuts, took the pose of the latter but changed the pair into two Rubenesque women. In the poem, the prostitute assigned to Gemini speaks of "being dedicated to love and am embraced as everyone sees." That doesn't sound like wrestling, but she also speaks of putting the "pazzo," the crazy twin, under her feet.

The half-body was also used in a 1482 printed edition of Hyginus' Poeticon Astronomicon, with woodcut prints, as below right. The engraved card opted for the more realistic depiction of the full body. (Leo, in contrast, was always shown with a full body.)

The end of the sequence returns to the last five cards of the 22-trump tarocchi, in the Florence-Bologna order with the call to Judgment by the trumpeting angel last.

The Sun is a departure from the lady with the distaff of the Florence-derived tarocchi, from one person working to two people conversing. That it has two people may be influenced by the TdM 1 (e.g. the Noblet, ca. 1650) or a predecessor. The man's dress on the Bolognese card is of a later style than in the Florentine. In the latter, the man's balloon trousers was a fashion of the early 17th century, whereas the culottes of the Bolognese card come from the time of Louis XIV (https://www.lovetoknow.com/life/style/trousers-through-history). The square collar, seen mostly on women, along with the bulbous trousers, makes him appear almost feminine. Apparently in Muslim countries these trousers were worn by both men and women.

The early World cards did not put maps on their depictions of the World; that idea, with Europe at the center of a wider world, reflects a later sensibility than cards with hills and castles, classical structures, or steepled churches. Some woodcut minchiates in fact showed hills with castles on them instead of the one or two buildings seen on the woodcuts (4th above, from a Fournier Museum "Paragona"). The focus on buildings, on the other hand, is already evident in the Rosenwald (middle above).

I have already commented on the Trumpets card and its difference between Bologna (first below) and Florence (Etruria, 2nd below), each with its own skyline and including, although in a different view, the engraveds (3rd), also from Florence. In terms of antecedents, I find no precedent for that custom, as opposed to the usual resurrected dead emerging from their tombs. But I can make a couple of other observations. First, minchiate is the only version where one angel blows from two trumpets. Here the precedents are first, that in prior woodcut versions of this scene, it is always one angel and not two. But second, there are a couple of early hand-painted ones with two angels blowing trumpets, namely the Visconti-Sforza (1450s) and Charles VI (1460s. 4th below). So a little of this and a little of that. Second, the angel's robe on the engraved is considerably more extensive than on the woodcuts. That of course gives room on the card for the Medici arms; but it also brings to mind Mitelli's version, an angel in flowing robes ascending upward.

I hope it is clear from these comparisons and interpretations that the engraved version is almost certainly earlier than the woodblock. The woodcuts are closer in style to the early tarocchi from which the deck arose, while the style of the engraveds has numerous affinities with the Mitelli tarocchino of 1660s Bologna. The engravings also use images of the zodiacal signs.

Th en there are the 3 and 4 of Cups and the 4 of Coins. Here we have Padovano's cards of 1547 (at right) to show how old the Florentine versions of those cards would have been (these are from a regular deck), against which the Bolognese self-advertisements in words would seem a modification.

en there are the 3 and 4 of Cups and the 4 of Coins. Here we have Padovano's cards of 1547 (at right) to show how old the Florentine versions of those cards would have been (these are from a regular deck), against which the Bolognese self-advertisements in words would seem a modification.

If we had access to more of the earlier cards, we would probably be able to find more examples. Here the decks of Lucca and Finale Ligure are instructive (mentioned at the end of section 3). While the suit cards conform to Florence, the trumps are sometimes like Florence's and sometimes more like Bologna's.

Florence's depictions, at least, continually changed in the roughly one century of time examined here. There is no reason not to expect the same earlier than the decks now extant. As for Bologna's, if they are so similar to one another it may be that they were all produced around the same time, mostly for export, perhaps historical conditions were such that northern European museums got their specimens just after a certain time, notably the end of the Medici dynasty and the introduction of foreign rulers from the north into neighboring Tuscany. What the museums have would thus be tourists' souvenirs supplemented by the small demand for imports that they would have induced.

I should perhaps comment on the little "rosettes" in the corners of some of the minchiate cards of every persuasion, as seen for example in the Papa One cards above. There is something corresponding in the Rosenwald sheet of c. 1500 - little "lunettes" in the corners of every other card, except in the case of trump 2 (the Popess?). There it seems pure decoration without further significance. In minchiate I am not so sure. It might indicate cards of greater value than the ones lower down in the same sequence. In the suits these rosettes are on the Aces, Kings, Queens, and Jacks only. In the trumps, they are on the twenty cards added to the tarocchi after the Tower, which might indicate their superiority to those preceding. That the rosettes are on Papa One and the Fool might indicate their special importance, too. The exception is again the Popess.

There remain many mysteries about the minchiate, and its visual features are deserving of more exploration, especially regarding whatever came before those designs that we see from the 18th century. These cards may hold some secrets about the early woodcut Florentine tarocchi and its relationship to some hand-painted cards of not completely certain provenance.

No comments:

Post a Comment