This blog is a five part essay on the woodcut minchiate decks of the late 17th-early 19th century, focusing on the visual imagery in the production in two centers, Florence and Bologna, comparing and contrasting the contributions of the two cities and elsewhere, to the extent they are similar.

I should warn you in advance that some of the decks I am focusing on, almost all of the woodcut decks from Florence in fact, are not very pretty, at least the ones that ended up in museums and research libraries. For one thing, some of them have clearly seen some use. For another, the cards would seem to have been made as cheaply as possible, probably to maximize profits in a situation where the sale prices were fixed in advance by the concession holder or government agency. The colors added by stencil are often like those applied by children before they learn to color inside the lines, and those lines themselves are from woodblocks either crudely cut or so worn out that impressions are illegible. As long as they could tell one card from another, it didn't seem to matter to the players. Hence these decks, except for a few cards have been generally ignored in the literature, even in studies specifically devoted to the minchiate of Florence. There are not even "reconstructions" available for purchase, much less reproductions. Most museums and libraries offer only limited views of the decks in their possession, whether online or in catalogs, in low resolution online and black and white in catalogs, and of just a few cards. Gallica and the British Museum are the major exceptions, for which we must be grateful. If there are higher quality specimens in private collections, they are not being shared with the rest of us.

Bologna produced better looking cards. There the game was not played much, players preferring their own game of tarocchini, with 22 tarocchi and 40 suit cards, the 2s through 6s being removed. Their minchiates were mainly for export elsewhere, even to Florence if the supply there ran short. The decks viewable online seem to have had little use, so probably were purchased by foreigners who had little idea of how to play the game.

The difference between minchiate decks and tarocchi decks is that minchiate (also called germini for part of its history) adds twenty trumps to the tarocchi decks and subtracts one. The twenty are Prudence, the three theological virtues, the four elements, and the twelve signs of the zodiac. The one subtracted is that which tarocchi called the Popess, which seems also to have been absent from the tarocchi in Florence by at least 1500, judging from a poem written around that time cited by Thierry Depaulis in his "Early Italian Lists of Tarot Trumps" (on the website academia, originally published in The Playing-Card, 36, no. 1, July-Sept. 2007, pp. 39-50, on pp. 40-41).

There are also some differences in nomenclature. We know what the cards were called at this time, the 18th century, mainly from the books written then about how to play the game, which I know mainly through the summaries given by Franco Pratesi (for a list, with links to both the Italian originals and my translations reviewed by him, see http://pratesitranslations.blogspot.com/). These books invariably refer to the cards just by number, except for the first five and the last five. Earlier at least some of the first five had the same names as in tarocchi. (Here see Nazario Renzoni, "Some remarks on Germini in Bronzino's Capitole in lode della Zanzara," The Playing-Card 41, No. 2 [Oct.-Dec. 2012], for "Empress," "Emperor," and "Pope" in the 1530s-40s.) But by the eighteenth century they were simply "Papa" plus the number from one to five: "Papa One," etc. The last five were called Star, Moon, Sun, World, and Trumpets. Since I am focusing on what is depicted on the cards rather than the game itself, I will use the generally accepted names, typically those of the tarocchi, for the cards the two decks have in common plus the usual names for the virtues, elements, and zodiacal signs, except for the first four and the last one, Trumpets.

My essay is divided into five sections, with all but the first two on different web-pages. The Introduction, which presents the issue to be examined, is here. Then comes "2. Bologna," again here but also accessible directly at https://earlypatternminchiate.blogspot.com/2024/08/bologna.html. Then comes "3. Florence," accessible directly at https://earlypatternminchiate.blogspot.com/2024/08/florence.html, or by clicking on one of the options at the bottom of the present page. For "4. Bologna and Florence," you click on one of the options at the bottom, or go to https://earlypatternminchiate.blogspot.com/2024/08/bologna-and-florence.html. "5. History," is at https://earlypatternminchiate.blogspot.com/2024/08/history.html. There I get into sources and interpretations, as opposed to just comparing visual details. Each section is complete in itself, but it is best to read them in succession.

In what follows, I have sometimes squeezed a lot of reproductions of cards in one row, as many as seven. Fortunately, the template allows for enlargement of the page on your computer. And I ask your forgiveness for the way many of them appear on the page. For those from the British Museum site (https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=minchiate), I simply took screen-shots of what was there without trying to straighten them. Someday I may have time to fix them, but at the moment I do not.

THE BUSINESS AT HAND

In 2019 Nicola Antonio De Giorgio wrote an article on the playing cards of Lucca that, almost as a kind of aside, also offered five criteria for distinguishing minchiates made in Florence from the same in Bologna.[1] These, plus a recent desire on my part to identify the provenance of a partial deck of 18th-century minchiate,[2] got me thinking: could these criteria be part of a larger, more general way in which minchiate woodcut decks made in Florence differ from those of Bologna, in the sense of a Bologna pattern and a Florence pattern, similar to how Tarot of Marseille decks differ between TdM 1 and TdM 2?[3]

The International Playing Card Society (IPCS) already has two pattern sheets,

called “earlier” and “later” minchiate patterns.[4] But the

sheet for the “earlier” uses a deck from Bologna and so does not

distinguish Florence from Bologna. As for the “later,” it uses a deck of

1926 made in Genoa from a version there, although the design, in its “later” version, is

one that was manufactured earlier in Florence starting

around 1820;[5] this "later pattern" also had an earlier version, also made in Florence, which the

pattern sheet credits to “the second quarter of the 18th century,”

but in fact began earlier.[6] The "later pattern," both late but especially the early, stylistically has little in common with most woodcut decks

of the 18th century, even if it does fulfill four of De Giorgio’s five

criteria for Florence (about which more later in this section). It offers more detail and sharper lines than the woodcuts, and its colored versions pay closer attention to using those lines to delineate differences in color.

As opposed to the "later pattern," what I am focusing on is the Florentine version of the “earlier” pattern, stylistically very similar to that put out in Bologna around the same time. Is there a distinct pattern in Florence that distinguishes it from Bologna’s woodcuts of the same period? I do not mean in every card, obviously, but similar to how the Marseille I and II differ, that is, in a significant portion of the cards, and not in every detail, but in commonalities across decks of two types.

I will start by summarizing De Giorgio. First, decks from Bologna feature

the Bologna skyline on trump 40 (Trumpets). He shows an example of the card along

with old illustrations of that skyline. There is an immensely tall tower rising in

the center and another, shorter tower leaning to the left of vertical and crossing behind the other one. These correspond to the Asilelli and Garisenda towers in Bologna. Decks from Florence, at least of the “later” pattern,

show the Florentine skyline, with the dome of the Duomo, Giotto's shorter tower,

and the River Arno flowing at the bottom.

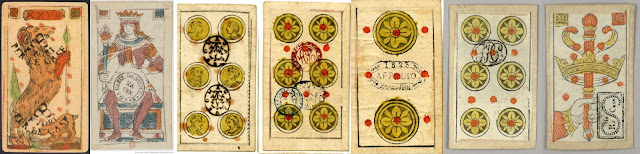

Second, in the middle of the 4 of Coins, Florence put an elephant, while

Bologna had the writing "carte fine" and either the name of the card

maker's insignia or nothing else. For Bologna, his card has "Carte fine

alla Colomba" in an impressive setting resembling a coat of arms, while for Florence the card had

an elephant and its rider. Third, the middle of the 3 of Cups has a

"probable lion" while Bologna had the words "carte fine in

Bologna" or perhaps just "carte fine." Fourth, the 4 of Cups,

Florence had a monkey looking at a mirror, while Bologna had the image of an

insignia of the card maker. Here are his illustrations of these points:

But how valid are these criteria? The last one rather obviously only applies to the “early pattern” decks, as all of the “later pattern” decks, also clearly of Florence, show all of the Kings bearded. Since there are two “later pattern” versions, I will show the kings of Cups and Coins from both.[7]

But the question can be raised again: do his criteria really work for all cases, even apart from the “later pattern” decks?The criterion most obviously affected is the skyline, which De Giorgio says applies in the case of Florence only to “late pattern” decks. It

is not hard to see why he would say that. Hardly anything can be made out on the Trumpets card of the deck ending in 41 on the British Museum (BM) website. [8] It is true that no high tower can be made out where the Bologna cards have one, nor a shorter "leaning tower" behind it (1st left below, BM deck ending in 39). but the lines of the skyline are so faint that it is hard to tell much of anything.

But there can also be a skyline on the card that does not clearly denote either Florence of Bologna, for example the one at left, from Plate 17 of Romaine Merlin's Origine des Cartes a Jouer, in Google Books, no page number, but p. 191 of the pdf, if you download the book). There is no dome, just a peaked roof. Some, with the same "Fama Vola," have a skyline that refers us to Lucca. Or the card might be missing from a deck we wish to identify. So how can we be sure that a deck satisfying De Giorgio’s criteria is from Florence and not somewhere else? Why should an elephant, a monkey, and a lion-like animal signify Florence?

One answer might be that if the same characteristics in other cards always fail to accompany the Bolognese skyline, and always accompany decks with no high tower, we can assume the same will be true when the requisite card is missing or obscure. Then we would have to find such characteristics. Another answer, perhaps more definite, is that Florence stamped

its cards in characteristic ways on one of the trumps, the exact one varying only occasionally, when a new tax concession period started. Stuart Kaplan addressed

this question in volume 2 of his Encyclopedia of Tarot; more recently, Giambattista Monzali has done the same.[11]

Many of the decks with the elephant, monkey, and lion-like animal have

characteristically Florentine stamps on the proper cards, even without the

visible skyline. Neither author address the tax stamps of Bologna. From looking at decks with "in Bologna" on them, I find just one with a stamp on a trump card, and it is merely a "fuori per le case" - out for the houses (on Aries, card 27, at http://a.trionfi.eu/WWPCM/decks07/d05114/d05114.htm. Many have no stamp at all; online, I see one with stamps on the 6 of Coins (https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1896-0501-40), and one with a stamp on the King of Batons (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105373422/f111.item).

The only difficulty with this second answer is that Florence, besides stamping its own cards, would have also put its tax stamp on cards it imported from Bologna. Franco Pratesi found a statement by the concession manager Domenico Aldini admitting to this recourse when Tuscany could not meet the demand itself, assuring his bosses that the tax was collected.[12] However, such imports would have been an exception rather than the rule; moreover, on many decks there was a second stamp on a different card, initially Libra, with the words “Stampa delle carte di Firenze,” or just the initials FCS.[13] Perhaps that was to guarantee that the deck was a Florentine production.

Another helpful clue is that certain trade-names were only used in one of the two cities: “Poverino,” for example, is characteristically Florentine. However, in many cases similar names were used in both cities: “alla Fortuna” in Bologna, “Fortuna” in Florence, etc.[14]

For Bologna, there remains a problem with that skyline in relation to its place of origin. The British Museum

(BM) has online scans of a deck with that same high tower, but also the peaked tower and ribbed dome characteristic of Florence; (2nd from left above, BM deck ending in 42); on its 4 of Coins we see the the words “carte fine di Roma (1st from left above), inside the same elaborate coat-of-arms-like setting as the ones with "in Bologna."[15] This deck meets all of De Giorgio’s criteria for Bologna otherwise. Another "di Roma" deck at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. (https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/search?query=minchiate) again satisfies all the criteria. Its 4 of Coins (3rd above) is identical to one shown in Yale's catalog of the Cary Collection that does have that card, again with the Bologna skyline (third and fourth below, from vol. 4, p. 47, deck ITA 61). Notice in particular what appears to be a date, "1803," more or less, below the word Roma in all three cards. Yet two of them have the Bologna skyline and the third likely did, too. Perhaps these

decks, too, can be said to be of the “Bologna early pattern.” A deck doesn’t

have to be made in one particular city to conform to a pattern, as the Tarot of

Marseille I and II abundantly show. Alternatively, these decks might have been made in Bologna for export to Rome. Are these decks variants of a Bologna pattern or a different pattern

altogether? We have to look.

For Bologna, there remains a problem with that skyline in relation to its place of origin. The British Museum

(BM) has online scans of a deck with that same high tower, but also the peaked tower and ribbed dome characteristic of Florence; (2nd from left above, BM deck ending in 42); on its 4 of Coins we see the the words “carte fine di Roma (1st from left above), inside the same elaborate coat-of-arms-like setting as the ones with "in Bologna."[15] This deck meets all of De Giorgio’s criteria for Bologna otherwise. Another "di Roma" deck at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. (https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/search?query=minchiate) again satisfies all the criteria. Its 4 of Coins (3rd above) is identical to one shown in Yale's catalog of the Cary Collection that does have that card, again with the Bologna skyline (third and fourth below, from vol. 4, p. 47, deck ITA 61). Notice in particular what appears to be a date, "1803," more or less, below the word Roma in all three cards. Yet two of them have the Bologna skyline and the third likely did, too. Perhaps these

decks, too, can be said to be of the “Bologna early pattern.” A deck doesn’t

have to be made in one particular city to conform to a pattern, as the Tarot of

Marseille I and II abundantly show. Alternatively, these decks might have been made in Bologna for export to Rome. Are these decks variants of a Bologna pattern or a different pattern

altogether? We have to look.Then there are the Kings of Coins and Cups. There are two problems. First,

how many of the kings need to be in a partial deck in order to satisfy the

criterion? One bearded king of Cups or Coins is not enough to say a

deck is from Bologna. Decks of the “later” pattern, or that of other cities,

have to be excluded. Perhaps it will be enough to specify a certain kind of

look, pose, and style of execution. For Florence perhaps even one unbearded

king of Cups or Coins is enough. We have to look.

The other problem is how to distinguish a robed, unbearded king with long

hair from a queen with the same attributes? It will not be a very helpful criterion

if there is no consistent distinction between the two in a Florentine pattern

deck. But of course the players would need to be able to distinguish them, too. The problem is easy to solve. If you look online at decks with an

unbearded King of Cups or Coins that also have Queens present, you will see

that the Queens of Cups and Coins have their elbows out and their Kings don’t (the two at left below are from Florence, Bologna the two at right.)[16] The Kings of Batons do have their elbows out, but in those suits only the Queens wear robes. Hopefully,

that will be enough to identify these cards correctly.

To proceed further, I will start by identifying decks that have “in Bologna” on their 4 of Coins and a Bolognese skyline; then I will compare them with decks that have “in Roma” on that card and decks with just “carte fine” and no city. Are they enough alike that we can say that they are of the same pattern, variants of the same pattern, or of different patterns? Then I will do the same with Florence. And then compare the two, bearing in mind the variants.

[1] “Le Carte da Gioco a Lucca,” The Playing Card 48, no. 1 (July-Sept. 2019), pp. 14-30, on pp. 24-26.

[2] https://forum.tarothistory.com/viewtopic.php?p=26479#p26479 and following, responding to the previous post, my translation of a note by Franco Pratesi concerning a partial deck of uncertain provenance.

[3] Thierry Depaulis, “The Tarot de Marseille – Facts and Fallacies, Part 2,” The Playing-Card 42, no. 2 (Oct.-Dec. 2013), pp. 106-120, on pp. 106-107. Online in Academia.

[5] For 1820, see Giambattista Monzali, “Minchiate Toscane, Part Two, The Playing-Card 50, no. 2 (Oct.-Dec. 2021), pp. 50-66, on p. 56. “An edict dated 20 March 1820 changes the card bearing the duty stamp, no longer the XXX but the XXIIII (Libra). From this moment on, the iconography changes, almost all decks are of the LMP type, giving the impression of being a simplified version” – meaning a simplification of the earlier LMP (Later Minchiate Pattern).

[6] See Giambattista Monzali, “Minchiate Toscane, Part One, The Playing-Card 50, no. 1 (July-Sept. 2021), pp. 11-26, on pp. 23-24.

[7] The two on the left are from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10336508z.r=jeucart%20minchiate?rk=64378;0, said there to be from ca. 1715. The British Museum (BM) has others online that seem to be from the same plates: at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=minchiate see those whose museum numbers end in 97, 48, 133, and 47. The other two Kings are from the “Minchiate Fiorentine” deck published by Meneghello, 1986, online at http://a.trionfi.eu/WWPCM/decks07/d05113/d05113.htm.

[10] Monzali, part 2, p. 55. The card is on p. 54, from a deck with “L. Mauriv-“ on its Knight of Coins, for Luigi Mauri.

[11] Stuart R. Kaplan, Encyclopedia of Tarot, vol. 2, pp. 247-249 for Tuscany; Monzali, part 1, pp. 19-22, the same. Neither says anything about Bologna. Many of the decks in museums have no stamp; those that do have it on the 6 of Coins.

[12] “Firenze 1766 - Domenico Aldini sotto inchiesta,” https://www.naibi.net/A/ALDINI.pdf, p. 2.

[13] Monzali, part 2, p. 50.

[14] Monzali, part 1, p. 22; Kaplan, vol. 2, pp. 219-225; Sylvia Mann, « At the Sign of …Italian style,” The Playing-Card 13, no. 2, pp. 52-55.